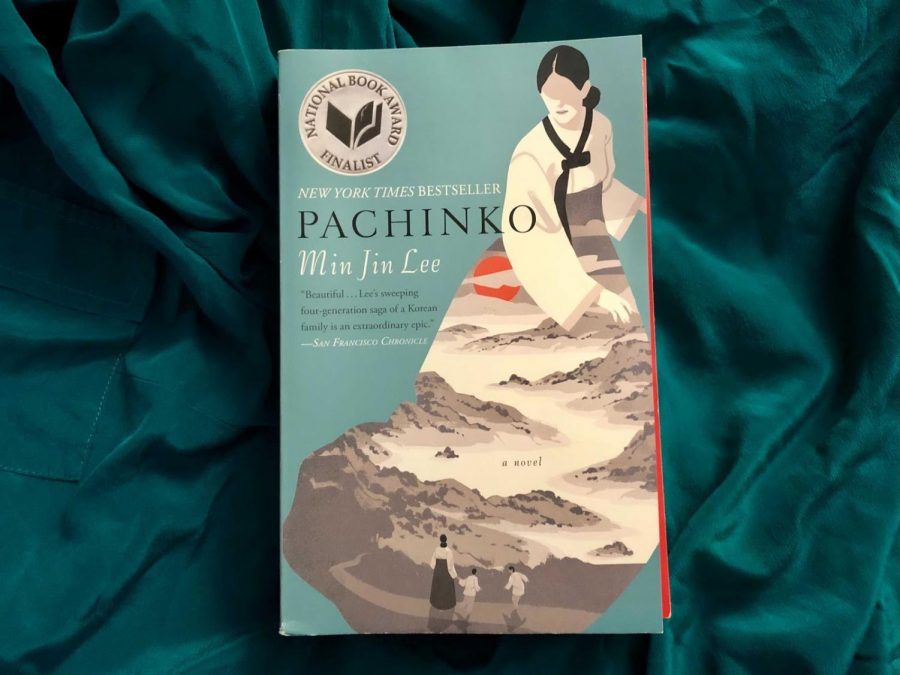

This book has become one of my new favorites.

“Pachinko” is a story that spans a century and follows the lives of four generations of Koreans. It shows how a family strives against all odds to make it out of poverty and to support themselves, but often at the cost of losing their original cultural identity. to make way for new traits that bear fruit for them in a foreign land.

The book begins with a wife and husband who own an inn and have a deformed child. The family lives in Korea — a country that was under Japanese colonial rule — in the 1920s. The child, however, is a hard worker with a heart of gold and comes to be respected by the entire town. Through a matchmaker, he weds a girl from a different part of Korea. The two eventually take over the inn and have a child named Sunja. As she grows up, Sunja becomes accustomed to working hard at home and accompanying her father on market errands. When her father passes, Sunja assumes many of his roles.

One day, Sunja is assaulted while running one such errand and is saved by a broker from the pier named Hansu. The two become friends and it isn’t much longer until Sunja is pregnant with his child. Unbeknownst to Sunja, Hansu has a family in Japan. Sunja, disgusted, decides to raise the child, Noa, on her own and cuts off all ties.

Sunja eventually finds herself in Osaka, Japan, where she has another child named Mozasu with a minister. From that point on, the story only gets crazier as they attempt to navigate Imperial Japan, where Koreans are scorned as less than dirtand Hansu eventually turns up in her life again.

The story follows Mozasu and Noa’s own children, too, as well as their experiences growing up in the 70s and 80s, and their subtle search for self. Though their family continues to expand in Japan, they are seen as perpetual foreigners who must get involved in horrible businesses — Pachinko, Barbeque and even the Yakuza — in order to get by. The title comes from the casino-like business that even the lowest Japanese did not want to get involved in.

Lee’s power in telling the story comes in her steady tone. The omniscient narrative is simple and fair minded. However, when the scenario calls for it, there is just enough detail to fully understand the risks every character is taking. Through this form of truthful storytelling, the fiction comes across as true in every essence, with historical accounts from outside sources only emphasizing the type of pain and hardships Sunja’s family would have endured if they were real.

As readers, we are able to know what this family has been through from the beginning, and for that we can carry their suffering and sadness, relief and triumph in our hearts. In the novel, Lee writes about a Pachinko owner: “He understood why his customers wanted to play something that looked fixed but which also left room for randomness and hope.” The same could be said of Lee’s novel — where we continue to flip the page, hoping that something comes from their endurance against all odds.

There is a word in Korean, han, that is equivalent to words like love or despair in English — it’s hard to describe but the weight of the word is heavy like cement. Han, though never used in Lee’s novel, is felt through the endurances of each character that are fighting desperately to survive; perhaps the most comparable word in English would be resentful sorrow. Han is often associated with families that were separated when Korea was divided into North and South, to mark the anguish and grief. It is said to be an aspect of Korean identity that one inherits, a modern post-colonial identity.

As a Korean-American, I feel it too. My mother’s family descends from what is known as North Korea, and when the borders were being created, my grandfather had narrowly escaped by trading spots with someone else who was supposed to go back to South Korea. From then on, my family had to create a new narrative for themselves and find a new community as the economy was still in shambles. When they moved to the United States because there was no chance for opportunity in Korea, they had to start over again, just like Sunja’s family and many others during this time of tumultuous conflict and restlessness in the Pacific. It is because of the war and constant invasions by other countries, and even conflict within the country, that I do not have family in Korea. Often, this loss seems to eat up my own understanding of what it means to be Korean.

There is a reason why “Pachinko” received so many rave reviews and became a top choice on the lists of so many prestigious reviews and magazines. It was a National Book Award finalist and Apple is working on a film adaptation. Not only does this book give you an idea of what it was like to live under Imperial Japan, but it offers you a sense of compassion for every man and woman who has sought to thrive amidst oppression. The story brings strength to all of us when we need it most, delivering hope to those suffering right now that there may be light at the end of the tunnel, even if we cannot see it now.