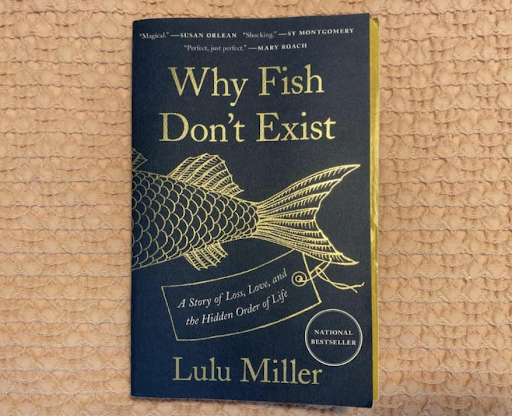

“Why Fish Don’t Exist” is a deep dive into the life of historical figure David Starr Jordan, a source of resilience for Lulu Miller, the author of the book and an NPR reporter. Jordan is a taxonomist well known for the 2,500 species of fish that he and his crew identified. Born in 1851, he grew up in rural New York and was infatuated with the natural world. Jordan’s life changed when he studied under biologist Louis Agassiz at “a kind of summer camp for young naturalists” on Penikese Island. This is where he makes his first acquaintance with the ocean and the animals that call it home.

The few months he spent working for Agassiz changed his life completely – he marries and has children. Jordan traveled to the Gulf Coast and Pacific in search of obscure fish, which were then preserved in mason jars and ethanol. He had a considerable collection until a lightning strike torched his study in 1883.

For anyone, the destruction of a collection you’ve devoted your life to is cataclysmic. It is an event that ravages and scars the heart so deeply that you wonder: can the soul heal itself again? Jordan grieves, but he returns to the ocean to start again. He travels around the world and is hired by Leland Stanford to be Stanford University president at just 40 years old, then remarries and has children again. Jordan’s resilience captivates Miller. In the aftermath of a difficult break up, she wasn’t sure where or who to turn to.

In other words, Miller was in need of a role model – historical proof – that you could overcome chaos. Jordan was able to overcome more than a lightning strike, but also the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake that toppled his collection of specimens at Stanford. Instead of succumbing, he frantically pinned name tags to the specimens. He was the perfect example of a man struggling with the lashings of entropy; one could argue he was even containing it.

Unfortunately, the same undefeatable optimism that gave him the strength to salvage his work and pick up all of the scattered pieces was also the same foolish pride that helped him justify the murder of others. Jordan believed the animal kingdom could be stuffed into a rigid pyramid.

In turn, Jordan became one of the biggest eugenicists in the United States. He published a thesis entitled “The Blood of the Nation: A Study in the Decay of Races by the Survival of the Unfit” in Popular Science magazine. His interest in eugenics was sparked when he visited Aosta, Italy, a town with people who had disabilities and deformities. Influenced by the teachings of Agassiz, who was also a believer of eugenics and even defied the beliefs of Charles Darwin, Jordan was concerned that allowing the unfit to reproduce with one another would lead to degeneration of the human race. With a 13 million-dollar donation from a friend, he eventually turned eugenics into law, ruining the lives of women that Miller later interviewed in the novel.

Miller’s source of inspiration for controlling her life turned out to be an egotistical maniac who believed he had the right to choose who could live and die. When Jordan passed away, it seemed he had bested the world by traveling the oceans and studying fish until the day he died, until some taxonomists, specifically clavists came along. Like an enclavist who believes in separating things into distinct groups (enclaves), these clavists were taxonomists who were reevaluating the way species were named and grouped.

These clavists realized that the category of fish did not exist, arguing that not all animals in the ocean are fish just because they’re in the ocean. Some “fish” are more closely related to us or a cow than they are to other aquatic species, just as not every mountain-climbing species should be named “mish” because they live in high altitudes. Jordan devoted his entire life to something that did not have any taxonomic relevance or afford any new information on the species’ evolution. Fish simply don’t exist.

In this book, there is a bit of everything – metaphysical inquiries, like can a fish exist if we do not give it a name? There are scientific psychological notes, such as whether positive optimism makes for a more successful person. There is the discussion of morality: does Jordan really deserve all the fame if many of his fish were caught by Asian American or Latino fishermen on the coasts of every continent? And there is a satisfying turn of the plot with every turn of the page – new information that puts the rest of the book into context. “Why Fish Don’t Exist” is a unique cross between a biography of Jordan, a documentation of Miller’s own struggles and the quantitative and qualitative data gathered by scientists to help put into perspective – are humans really, truly able to be in control? I wholeheartedly recommend everyone to read this book because it discusses so many important issues with a sensitivity and exactness that only science and writing could make together.