When false headlines go viral in seconds and deepfakes blur the line between truth and deception, media literacy has become a survival skill — especially during election season. Understanding how to sift through an overwhelming flood of information is crucial to making informed decisions at the polls.

Media literacy refers to the ability to critically evaluate, analyze and interpret the information we encounter across various media platforms, enabling informed decision-making and responsible media consumption. Its use has become more important than ever, with studies showing only 40% of young people were taught how to understand media messages.

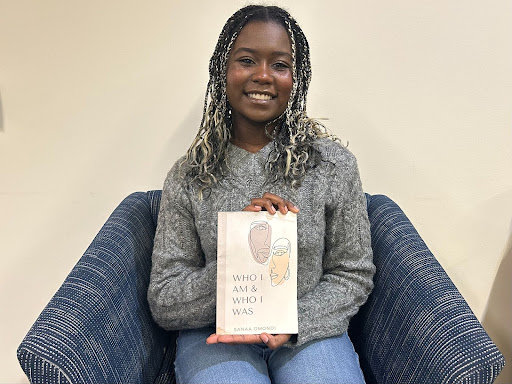

The Torch spoke with Dr. Elisabeth Fondren, associate professor of journalism at St. John’s University, to discuss the rising importance of media literacy. She shared key strategies to identify misinformation and emphasized the role young voters can play in countering its spread.

Much of Fondren’s research is based on propaganda and the history of journalism. This year, she’s particularly focused on helping students understand how their media consumption can be important decision-making tools.

“News literacy relates to this idea that we want our students to be engaged. We want them to take part in the democratic process, and we want them to participate and make their opinion heard. Mass media is one important way that we learn about politics,” she said.

“There’s that dynamic that we want to participate in democracy, but we need to know how to do it. And then media often gives us this imperfect picture of our reality.”

Media Literacy Strategies

In her classes, Fondren asks students about what she calls the “news diet.”

“I ask them, ‘What do you read? Where do you get your news?’ I think it comes down to developing some sort of awareness, or training to become critical thinkers and use information in a way that sometimes rejects what senders of a message want to say,” she said.

Her biggest advice when consuming news is to “investigate the source.”

“Make sure that whatever piece of information about politics you’re looking at comes from a source that has a reputation for accuracy. If you’re unfamiliar with an organization or a news outlet, you can always look on the website or social media on the about section. If they’re interested in providing quality information or journalism, they would have information about who is behind the stories.”

Fondren also advised readers to always keep their guard up.

“Just because your friend or family member shares information with you via social media, that doesn’t make the story true,” she said. “Trying to take that kind of personal element out of investigating the reliability of information is important because the way that disinformation and misinformation campaigns are designed is to engage the audience.”

Spotting Misinformation

Fondren spoke about the “markers of quality journalism,” and how people can scan any story to decide for themselves.

One of her biggest points was to see if an article is news or opinion. She finds much of the misinformation online are opinion pieces “disguised” as news articles.

“Is this written to promote a certain candidate or a certain policy? Or is this hard news and just facts?”

Another marker is sensational headlines, commonly known as dramatic or clickbait titles. They often feature exclamation points, something not commonly used in news stories.

She also warned of artificial intelligence (AI) images and videos, increasingly used in the media.

“That type of media contact gets incredible traction online. So people look at it, they share it.”

Aside from larger markers, Fondren acknowledges the simplicity of scanning these pieces.

“You should have a clear name [of the writer] and be able to click on it and see, okay, is this somebody that you trust, or, is this information presented as just a visual.”

She lastly differentiated news as a means to inform, rather than a product.

“Journalists want to inform and influencers or AI bots want to sell something — whether that’s a message or product. Information is not really their top concern. Their concern is, ‘Am I getting advertising dollars? Are you actually paying to buy this product or donate to this campaign?’”

She encourages students to utilize tools like FactCheck.org, PolitiFact and Snopes to fact-check and indicate media bias in news.

Navigating Election Season as a College Student

While it can be difficult for young people to interact with others politically and stay informed, Fondren offered advice for students.

“Talk to friends, classmates and roommates about how you engage with political information. It doesn’t have to be heads-on.”

She encourages young voters to take part in University initiatives, like voting drives and watch parties.

“For many first-time voters, it comes down to very basic information. ‘How does voting work? Where do I go? Do I have to bring anything,’” Fondren said. “This is even more preliminary than ‘Who will I vote for?’”

While social media can be a tool for misinformation, it can also be “democratizing.” Fondren illustrated voters’ roles as gatekeepers — the power audiences have in shaping which news stories gain prominence.

“We can research, investigate and make up our minds so we have unlimited choices in how we really assess information.”

“One point that comes from political communication research suggests that when we look at the way people use their phones to read about politics, we see that phones have increased access to political information and political learning. But at the same time, research suggests that we learn less from our phones when we engage with political news.”

Fondren encourages students to view news on bigger screens, to open numerous tabs to maximize the way they get information.

“You don’t have to pick up an actual newspaper anymore, but actually looking at your phone and engaging in this lateral cross-checking of information is important.”

The 2024 presidential election is on Nov. 5. For a full guide to voting registration and deadlines, click here.