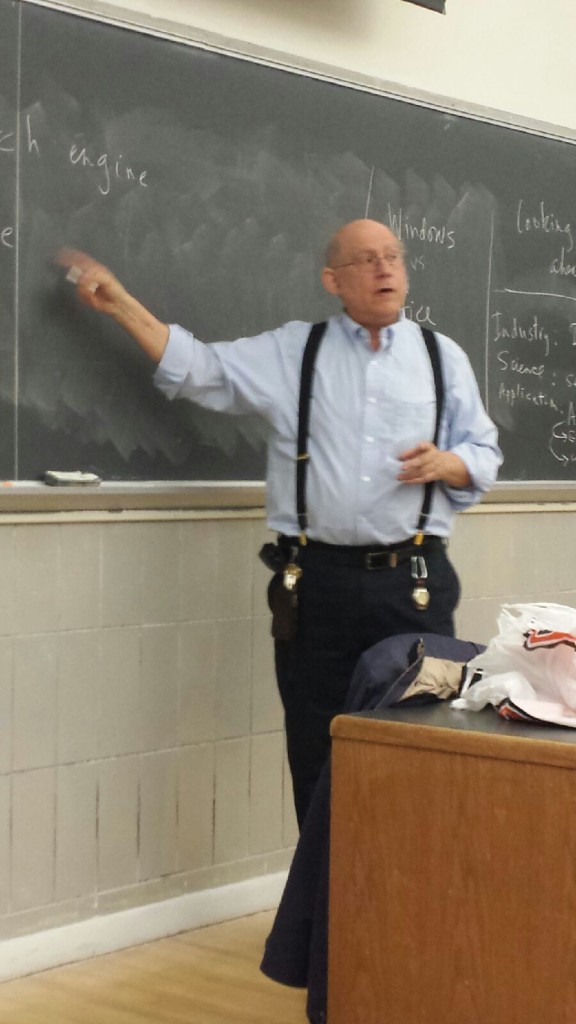

With 40 years of teaching experience, roughly 35 of which were spent at St. John’s University, Andrew Russakoff was recognized as No. 14 of top university professors by RateMyProfessors.com for the 2012-2013 school year.

The ratings are compiled through a five-point Likert scale as well as a binary scoring system for students to rate professors. Russakoff though was dismissive of the recognition.

While acknowledging that through various times in his life, he defined himself in different ways, including a bagpipe player, a graduate student at Oxford, a father, or a band member who played at the Waldorf Astoria, he recognizes that his role today is to be a part of that development in his students.

According to the computer science professor, one’s college years aren’t defined with the obligation to attend classes, the often “sophisticated” textbooks and the tests that follow.

It’s a lot more complicated than that so he doesn’t care if his students don’t show.

“Life is complicated when you’re a college-aged person, it really is,” he said. “And I’m not so sure that everything that happens in the classroom has precedence over all those other things.”

So even while teaching a largely technical and fact-based course like Computer Information System, Russakoff’s teaching philosophy includes putting the subject into context.

“He tells it like a story,” freshman Cynthia Morris said. “Even when he was talking about Microsoft and everything, it wasn’t just timelines and dates. I don’t even know what dates they took place in but I know the order in which they happened and I know what happened.”

Although Russakoff has a mathematics degree, he comes from a liberal arts background at Columbia University that is strongly devoted to a general education and a core curriculum. So his philosophy as a professor is to broaden the sometimes narrow perspective of courses like Statistics and CIS and incorporate outside forces in its framework to help students understand the subject.

“So I think, how am I going to sell this stuff?” Russakoff rhetorically asked with a higher-pitched voice. “And I think the way I do it is – they are far more engaged if I talk about the history of the computer industry. How did it happen that the IBM personal computer was such a big seller when there were 10 other computers on the market that were better and easier to use?”

However, Russakoff lowers his tone at the realization that the “national mood” is shying away from the importance of that context and is prioritizing the “specific” task of landing a job. That changing vision strongly resembled his experience at Oxford, where one specializes in their field from the start and through their education.

Yet a duty he still struggles with is appealing to the varying and inconsistent interests of his students that do not always include what he teaches. He realizes that a class on how to perform certain database management functions is not “intrinsically” engaging.

A majority of comments on RateMyProfessors.com emphasized how class with Russakoff will only last a maximum of 40 minutes. Russakoff explained that those varying interests, along with the energy of his students, dictate not only how long he will teach for but also create urgency for engagement and collaboration as a class.

“I say come to class,” Russakoff said. “If you come to class I could take you from where you are to where you ought to be. But I need you here. And when you’re done, I’m done too.”

Morris was quick to comment on her professor’s decision to keep the class for a short period of time.

“It’s not like he keeps you for 40 minutes and you’re missing stuff,” she said. “He keeps you for 40 minutes and he gives you all this knowledge and you understand what he’s saying. And you don’t have to worry about memorization because you have actually learned it.”

Sophomore Amy Shen explained his passion is contagious.

“He’s very passionate about what he teaches,” she said. “First, he understands what he teaches. Then, he gets students engaged in what he teaches.”

In his opinion, a way to engage his students is to not present information as mere facts or as needing to be solely “a, b, c or d,” but to allow his students to participate in a way that is good in and of itself.

He immediately gave out a powerful laugh at the memory of an answer to an extra credit question to write a poem about linear regression. Not only did he not expect the poem to rhyme, but he never imagined a student would fulfill the requirements of a haiku.

Staying true to the 5-7-5 syllable count per line, a student wrote: “Graphs or formulas/ even computer printout / regression still sucks.”

Russakoff acknowledged the fact it was not the “nicest expression,” but he was much more impressed with the how the student managed to put the pieces together to then still say ‘I just don’t like this.’

At the end of the day, Russakoff says he does not feel threatened by the importance of his job. Because although it would be great if he manages to engage his students in his interests, it is not a flaw on either side if that does not happen.

“I’ll show you a piece of something that got me where I am but I don’t want you to feel like, well if you’re not interested then we have no business,” Russakoff said. “You’ll learn the language and you’ll learn the piece, but now, what are you interested in? What motivates you?”