After the buzzer sounds and the clock runs out on his life on earth, Mel Davis hopes to reunite with his old friend. By then, he may have an answer to a question he has asked himself for years. “Why” is a word that crosses his mind nearly every day.

Why was life so hard back then?

He wishes he had an answer. That was just the norm.

Why did one of the greatest players in St. John’s history have to go through such things?

He can’t even begin to think about it, let alone talk about it.

There have been plenty of chances for him to be recognized. So, why the delay?

He hopes to learn. In the meantime, he will continue to share the lessons that were passed on to him.

The questions are always rhetorical, a replay of the decades of hardship he has dealt with. Maybe the answers to what he ponders will come around some day. For now, he’ll keep waiting.

Worries often alleviate themselves and minds are put at ease-at least that’s what is hoped for-as time carries on. The ability to search and speak for the voiceless becomes a race against the clock, the excavation for truth an unrehearsed ritual that never ceases to let up.

For years to come, Davis will continue to dig and press and reiterate the meaning of his friend’s life, the one that combated 85 years of hatred and blackness with dignity and reverence that he hopes will one day reach the rafters of basketball heaven.

And hopefully, that time will come sooner rather than later.

…

Mel Davis occupies a window seat toward the back corner of a restaurant in Manhattan’s Upper West Side, the black and white checkered flooring complementing the painful and grainy memories he prepares to relive.

He’s mellow and unfazed, his white dress shirt and grey suit pants unraveling off his 6-6 frame as he lifts himself out of his fancy red chair.

It’s a few minutes after 12:30 p.m. on an unseasonably warm Thursday in mid-February. Davis had just come Midtown, making his way towards the evergreens of Central Park just off Columbus Ave.

Soft-spoken but direct and unafraid to say what’s on his mind, Davis reflects on the time he spent in Queens as a three-year student-athlete.

He hasn’t the slightest interest in reminiscing about his outstanding basketball career. At St. John’s he averaged 20.9 points and 17.4 rebounds per game in two years of varsity ball. His tenacity on the boards places him eighth on the school’s rebounding list. Nor does he wish to discuss being drafted 14th overall by the Knicks in 1973.

“What I’m going to talk about today means a lot to me,” he said as leaned forward in his seat.

What Davis revealed was the untold story of a man that changed St. John’s University. A man who dedicated himself to the youth and his community, risking his life in the process to play the sport he admired. A man who changed St. John’s forever, but also one you may have forgotten about after many years.

If you have, you are not alone.

Davis has a significant story to tell, and he wants everyone to know about it.

…

An older black man sat in the living room of his brownstone house in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, collecting his thoughts and commemorating the old days when St. John’s campus inhabited his borough.

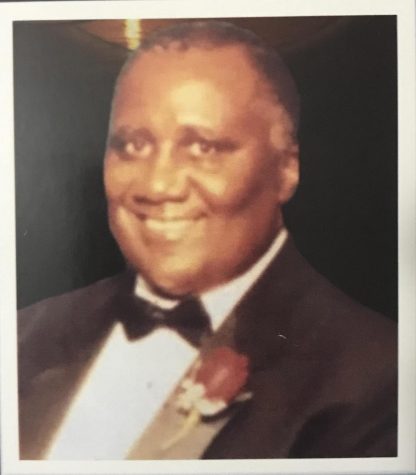

His name is Solly Walker. He’s a handsome, dark-skinned gentleman with rounded glasses and the same smile he boasted when he first stepped on the hardwood as a member of Coach Frank McGuire’s Redmen.

The difficulties Walker experienced as St. John’s first black basketball player and one of its few black students in the early 1950s are hard to talk about. They’re even harder to forget.

In 2008, he addressed a large crowd at the 10th Annual Frank McGuire Awards Dinner. Walker revisited one of those moments, detailing some of the most unfathomable parts of his life.

Before he officially stepped foot on campus, McGuire informed Walker and his parents that the Redmen would travel to Kentucky to play Adolph Rupp’s Wildcats. Walker, who grew up in the south before moving to New York as a kid, was just as hesitant as his parents. They didn’t want him to go. His father told him he wouldn’t let his son travel to any such place under hostile circumstances.

“Mr. McGuire assured them that wherever the team went, I would go,” Walker recalled.

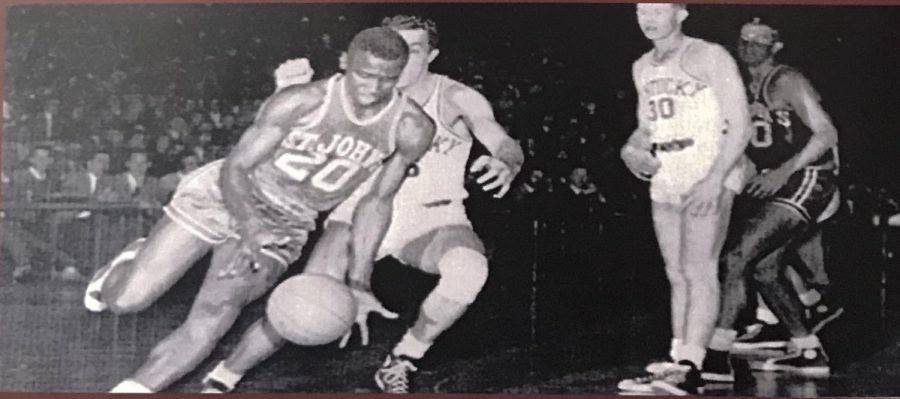

The day came with the unexpected standing ahead of him. It was Dec. 17, 1951. A Monday. St. John’s was set to play Kentucky in front of thousands of fans. Hours ahead of the contest, Rupp called McGuire with a harsh warning.

“You can’t bring that boy down here to Lexington,” Rupp said on the phone.

McGuire, unwilling to back down from playing the No. 1 team in the nation because of his black player, retaliated with his own threat.

“Then cancel the game,” he said. “Cancel the game.”

Rupp refused, and the game went on as scheduled. The Redmen traveled by train, arriving in Lexington around 2 a.m. Having not eaten for eight hours, the team found a diner.

“Of course, they said ‘Sorry. I don’t care who you are. You can’t come in here and eat,’” Walker said.

McGuire, along with coaches Buck Freeman and Dusty DeStefano, accompanied Walker to dinner so he wouldn’t be by himself.

To the kitchen they went.

On game day, Walker admitted to starting off too fast. He hit his first three shots and six of his first seven. “Then I ended up in the tenth row,” he joked. “That’s one thing you look out for. They bang you up and you retaliate. Now, you’re out of the game.”

Lou Carnesecca, the winningest coach in program history and an assistant at the time, remembers all five Wildcat starters converging on Walker and hitting him right after he scored his first bucket.

He was forced to leave the game-an 81-40 loss-with an injury. More slurs and insults were thrown his way as he exited Kentucky’s Memorial Coliseum.

In the years leading up to and following Walker playing on their home court, the University of Kentucky did not accept black undergraduates to attend school. It wasn’t until the landmark 1954 Supreme Court case of Brown v Board of Education that the University admitted its first black undergraduate student.

By all accounts, Walker was the first black player to play against the Wildcats in Kentucky.

“The crowd treated Walker, the first Negro to play in the Coliseum, like any other player,” read an Associated Press game recap from that day. “And he got a big hand when he went out for a rest in the second period.”

Kentucky wasn’t the end of Walker’s daily reminders that he was a black man in segregated America. When asked about the most chilling story Walker told him about what he experienced over the course of his lifetime, Davis thought for a minute and simply shook his head.

“I can’t tell you that,” he said. “In 1950, it was different. The world was different back then. A lot of things were just okay to do.”

As tough as life was for him, Walker never let his emotions show. He never raised his voice or showed anger. His smile and presence commanded a room. His willingness to help stood out more than anything. According to Davis, Walker had one standard, and one standard only: excellence.

Before his death on April 28 of last year, Walker made sure to always live up to the promises he not only asked others to keep, but that he made for himself.

…

Solly Walker was born on April 9, 1932 to Zodthous Walker and Eva Utsey in South Carolina. He moved to Brooklyn as a kid, where he starred at Boys High School (now Boys and Girls High School) on Marcy Ave.

He enrolled at St. John’s in 1950 and led the freshman team to a 17-2 record, averaging 15.1 points per game. In 1951-1952, his first year on the varsity team, Walker contributed 4.4 points and 3.8 rebounds.

In his junior campaign, he scored 7.0 points and grabbed 6.0 boards before a career-best 14.0 points and 12.2 rebounds per game as a senior.

After graduating with a degree in Business, Walker was taken in the seventh round of the 1954 NBA Draft by the Knicks. Instead of continuing his basketball career, Walker returned to St. John’s and received his Master’s degree in Education.

“I started teaching in one of those schools-those special schools-where the young men who were not wanted by the principal would be sent,” Walker said. “This was a challenge, which we accepted.”

He taught Hector Camacho, a former three-weight world champion boxer, and another unnamed Olympic champion.

“I had many all-city basketball players, many civil servant workers,” Walker said. “These are kids that society said could not function in the world in which we live.”

Walker knew how life would be for students, particularly minorities, in school and in society. He refused to send them out by themselves. One of the kids he looked after most was Davis.

He passed many of his lessons down to him. Davis has carried those practices with him for over 50 years since first meeting the man he calls his role model back in 1967.

From the moment he entered college to when he graduated, Walker always reminded Davis to keep his head high. Nobody could ever tell him anything if he lived life with no regrets.

“Plan A will have many obstacles, peaks and valleys,” he remembers Walker telling him. “Always have a Plan B.”

He taught and eventually served as principal at P.S. 58 (now P.S. 35) Manhattan High School on W 52nd St. While he dedicated himself to outreach through education, his heart never left Brooklyn, the place where the legendary tale of his remarkable life began.

“He changed communities,” Davis said. “He worked at a community center right after school. I can’t tell you the hundreds of players-and I know a lot of them-whose lives he influenced.”

There’s a lot of his mentor’s life that Davis and other influential figures want people to know about. Some of school’s most prominent figures praised Walker on his philanthropy and work outside of basketball.

Carnesecca noted how great of a player Walker was. More than that, he said, he lived an exemplary life.

“Solly was really well-respected and a man of quality,” Carnesecca said in an interview. “He was a great addition to our basketball tradition. More importantly, he was a great person, a sweetheart of a person.”

The school inducted Walker into the St. John’s Athletic Hall of Fame in 1993. He was also presented with the Trustees Award by the NYC Basketball Hall of Fame, according to RedStormSports.com.

“He was the first,” Davis said. “He gave his heart. He gave his wherewithal. He gave his everything with class and dignity.”

As he increased in age and health problems suddenly arose, Walker found himself in need of medical care.

Hospital visits were hard on both he and Davis. Walker eventually told him to not come anymore. The distance Davis traveled was too far. They opted for communication over the phone instead. Many of his phone calls came from the man who first recruited him.

“Solly was always grateful for the phone calls from Coach Carnesecca,” Davis said.

One conversation with Walker in particular about his storied life captured how much both men cared about an honor from the University.

It happened in Walker’s living room. As he reflected on that day, Davis sat up in his chair, crossing his arms as his eyes made contact with the ceiling. He takes a minute to gather his thoughts before speaking of a dilemma that never escaped his friend’s mind.

“I used to go to his house and just sit with him,” Davis said. “He couldn’t walk very well. He was in a wheelchair. He would reminisce all the trials and tribulations he had to go through. He just wanted to vent. He wanted me to know.”

The tears falling from Davis’ eyes depicted the longstanding years of pain that surrounded him and the Walker family. His canvas of answers still remains bleak and the future-although slightly more hopeful-is still hard to envision.

Davis’ heart still wrenches when he thinks of Walker feeling lost and alone. His voice now trails off into the distance. Walker, never one to shy away from the truth, looked the man he viewed as a son in the eye. He never evaded the thoughts in his mind, even if they hurt to hear.

“Mel,” he said. “I thought they forgot about me.”

…

41 years ago, in the public housing projects of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Davis heard a knock at the door. He was alone, not expecting a visitor that day. He opened it to find a 6-foot-4 figure filling the frame.

“His presence and his stature were just unbelievable,” Davis recalls of meeting Walker. “He asked if he could come in. He wanted to talk to me.”

Walker was 35-years-old at the time and had watched Davis dominate at his former high school. He wanted him to attend St. John’s. “He encouraged me to visit all the schools I wanted to visit,” Davis said. “At that time, you could only visit five.”

He toured St. John’s last, as instructed by Walker. Davis’ college choice was up to him, but if he had his sights set on another school, Walker would tell him why St. John’s would be a better match.

“The media, two professional teams and being close to home are some of the plusses of playing at St. John’s University,” Davis said of New York. “It was close to home. And I could be a star, a big fish in a little pond.”

After visiting with Carnesecca, Davis was set on attending St. John’s, committing on the spot.

Over the years, he and Walker never lost contact. Walker attended his games and always made time for him. Even when Davis went to Europe to play professional basketball in Italy, France and Switzerland, they wrote to one another and kept in touch.

“He talked a lot about being alone,” Davis said Walker recalled about his playing days. “When you’re playing on the court, you’re supposed to be playing against five men. But he said he had teammates that he didn’t think were that supportive.”

Constantly surrounded by a cyclone of isolation, Walker often overheard the whispers from guys he shared the court with.

“He heard comments like, ‘Well, we can eat there,’ or ‘why don’t you go over there? Find a YMCA where you could sit,’” Davis said. “Those kinds of things I’ll never forget.”

One day at an event several years ago, a St. John’s alum approached Davis, wanting to know about Walker. When he started asking members of the St. John’s community about him, Davis noticed a common trend developing.

They all thought he was dead.

“That’s when I really wanted to enlighten the St. John’s family and fans of Dr. Walker’s presence and his meaningful contributions to St. John’s,” he said.

Ever since, he has advocated for more awareness about Walker’s life. Next season, the University will retire his No. 20, the same number Head Coach Chris Mullin wore during his four playing years.

“[Mullin] has been very instrumental in trying to get his uniform retired as well,” Davis said. “Plus the fact that Chris wore the same number. I think that would also generate tremendous interest. If you see two No. 20s up there, and two different names, that will generate a topic of conversation.”

Davis is optimistic that with the support of Goff, Mullin and Carnesecca, a date will be set to retire Walker’s jersey. “I hope there will be a wonderful celebration where all St. John’s athletes, male and female, fans and alumni, can come together to celebrate the life of Solly Walker,” he said.

In a statement to The Torch, Goff called Walker a hero to St. John’s fans and supporters across New York. He echoed the sentiments of those who knew Walker best.

“To accept the responsibility that comes with being the first at anything shows the courage he possessed,” Goff said. “I can’t imagine how difficult his time was, but through his perseverance, he provided an example of what could be and what should be. His actions have allowed many individuals the ability to better their lives.”

It was recently announced that Walker will receive the Joe Lapchick Character Award in September. The award, which recognizes basketball figures “who have demonstrated honorable character throughout their careers,” is awarded annually. Davis was asked by Walker’s daughter, Debra, to accept the honor on the family’s behalf.

“That’s significant,” he said. “That’s a very nice start. That will lead right in to his uniform retirement.”

…

Nearly seven decades after he first stepped foot on campus, Solly Walker’s impact has resonated far beyond St. John’s.

Months before Walker matched up against Kentucky, Earl Lloyd was drafted by the Washington Capitals and became the first black player to play in an NBA game. Lapchick, a former St. John’s coach and Original Celtic, drafted Nat Clifton, the second black player to play at the NBA level.

To Davis, Walker should be remembered and mentioned in the same breath.

“His significance is unbelievable throughout the country,” he said. “St. John’s had Solly, then Columbia got a black athlete. Then NYU got a black athlete. Then Fordham got a black athlete… It just blossomed after that.”

Davis estimates that when he played for St. John’s in the early 1970s, minorities accounted for two percent of the student body. 20 years earlier, Walker could probably count on one hand how many students looked like him. Around that time is when he first built a relationship with Carnesecca.

Before Walker arrived at St. John’s as a student, Carnesecca said he familiarized himself with the incoming ballplayer while he was still at Boys High and as the school began looking at minority players.

“I really got to know him when I became assistant coach at St. John’s,” he said. “That’s when I got to recruit some African-American basketball players.”

According to the University’s 2016 Institutional Research Report, 42 percent of students are minorities or of two or more races. Davis was shocked at the number, applauding St. John’s for boasting such statistics.

He still wishes every student knew about Walker and his influence. At the very least, he aims to spread the messages Walker passed down to him to the students of today’s generation. “That’s why I want to encourage St. John’s to do what they’re doing,” he said.

Walker wanted the best for everybody who followed in his footsteps and attended St. John’s, not just athletes and black students. He opened doors that were once slammed in his face, just to ensure life was better for those after him.

“He wanted to make sure kids got that piece of paper,” Carnesecca said. “A degree when they graduated.”

Not once does Davis recall hearing him raise his voice, belittle somebody or get angry. He shed the occasional tear and hinted at frustration, but never pointed a finger.

This in spite of the fact that he talked about living in a world where many felt he didn’t belong.

“Every faculty member, every student,” Davis said. “And every alum should know his story.”

…

Before he turned to walk back down Columbus Ave., Davis stood still, his baseball cap scraping the sky that blanketed the busy Manhattan crowd. The clock had just struck 3 p.m. As Davis awaited the walk signal on W 85th St, he took a look around before his final words.

Before stepping off the podium ten years ago, Walker, as custom for him, thanked the crowd. Not for being present, but for staying patient.

“I hope to see you next year,” Walker said before ending his speech.

50 years ago, Davis experienced many of the same things Walker did, but he didn’t care to talk about them. Instead, he used his voice to educate and advocate, the patience Walker demonstrated carrying over to the legacy he left for those who came after him.

“This is about Solly,” he said.

The legacy Walker left behind will always remain at St. John’s and within the communities he built, people he inspired and words of encouragement he always graciously spoke.

Davis desires the day when Walker, the man he calls a prince, finally gets his credit. It’s long overdue, he says. For him, it’s important for the St. John’s community to know about his legacy.

“He is a pioneer,” Davis said. “He is the beginning.”

The light finally turns green. He leaves just as he arrived, strutting back to Midtown with poise and elegance. His red sport coat flows as he gaits among the crowd.

Even as the view of his briefcase trails off as the street numbers fade away, his broad shoulders and white cap still subtly shift through the crowd.

Mel Davis won’t lose sight of the lessons he’s learned over the years. He has no regrets and is full of promise. He peacefully disappears, but his head remains high far into the unforeseen distance.

Just like Solly.

Photo Courtesy/The Walker Family

Photo Courtesy/The Walker Family

Walker and his wife, Minta.

Ernie koglmeier • Mar 30, 2018 at 2:03 pm

God bless Solly and every person forced to endure such treatment in their lifetime. God bless those that see people for who they are, not what they look like. Every basketball player from St. John’s should be given the history of Solly Walker to help them realize the greatness of one of the basketball greats who went before them. Ernie k. GO JOHNNIES

GA • Mar 28, 2018 at 1:30 pm

WOW. Thank you for a great article. My dad told me about Solly but I never knew about the Kentucky game. Thank you Mel. This was very much appreciated and I look forward to seeing #20 being retired again.

Perhaps #20 should be reserved for a special senior player and not be given out the way it has the last 2 seasons.

CW • Mar 2, 2018 at 10:41 am

Outstanding job done. This was very interesting to me. The words were well said and the story had so much inspiration as I read it. The sports editor did a wonderful job with his writing,well put together and the before and after pictures that followed the story. I must say if readers didn’t know about this star basketball player before ,well they certainly know of him now and all that he did and accomplished in his years. Again, I would like to say what a wonderful well put artilce the sports editor has done. Continue to grow with your journey. Congratulations. So pround of you.

Joe Passabet • Mar 1, 2018 at 11:31 pm

Mel, I was the twelve man on the 69-70 freshman team. I was the one who wore glasses. It was great practicing everyday with you big stars. Tickets to the Garden; to Alumni Hall. Bus rides with the team. Frank Mulzoff was our coach and worked for my Dad years before. I’m sure that’s how I made the team. What a pleasure to read about your hero…he is a SJU hero. Thank you!

M. Walker Jr. • Feb 28, 2018 at 11:59 pm

Thank you Mel for this very humble eloquent article about my Dad! We know how much you meant to him and embrace you just as he did. Again thank you!