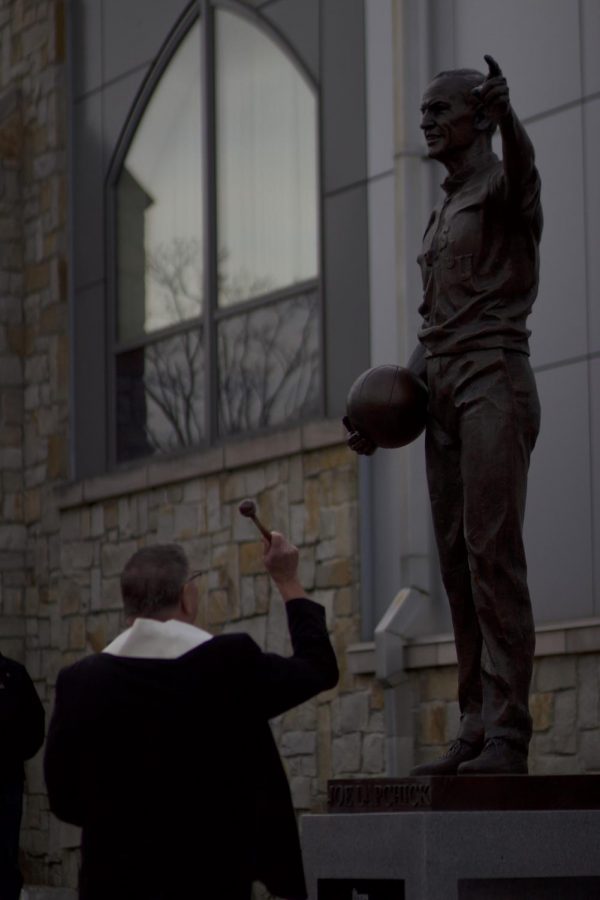

At his base, Joe Lapchick stands just three feet tall. The words inscribed below his feet commemorate his lifetime journey of changing basketball and the world both on and off the court.

Above that is a seven-foot-five-inch figure, a dominant man pointing toward the arena that now houses the St. John’s basketball teams. He weighs 4,000 pounds, a basketball in his right hand and a whistle hanging from his neck. A slight, detailed grin is sketched on his face as he glares into the distance.

Many people know about the man who towers over the walkway between Carnesecca Arena and Taffner Fieldhouse, but not many know about the one man sculpted this statue and hundreds of others seen around the world.

About 90 miles away in Toms River, N.J., Brian Hanlon carefully sculpts his masterpieces his studio, which sits on a chicken farm. He has about 300 around the world, ranging from Jackie Robinson at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, Calif. to Our Lady of the Rosary in Puerto Rico.

But when former St. John’s Athletic Director Chris Monasch approached Hanlon about creating a statue of Lapchick, he could not pass on the opportunity.

“Joe was more than a coach,” Hanlon said. He’s a pioneer in basketball in many ways, and that is as important as his basketball coaching.”

The history that Lapchick embodied presented itself at a time when racial tensions were high. He coached Solly Walker, who played for St. John’s and was the first black basketball player to play on the road at the University of Kentucky.

Lapchick, who also played for the Original Celtics and coached the New York Knicks, drafted Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton, the first African American to play for the Knicks and one of the first to play in the NBA.

“The story really is a labor of love,” Hanlon said. “I love stories like Joe’s because they’re educational and inspirational. Both in the same breath.”

Lapchick’s statue took Hanlon about eight months to create. He typically tries to work on about 15 per year, but the numbers vary. The team at his studio in New Jersey – which he refers to as his “mean machine” – ranges from six to 20, depending on the project and the complexity of the design.

The process is difficult, especially when working on several statues at once as Hanlon does. They create an image to scale from clay. Their work starts from the depths of the earth – literally. With dirt as the foundation, the team assembles each intricate area with a series of steps.

“We use mud like clay from the earth and we make an image,” Hanlon said. “From that image, we make a mold. From that mold, you can make waxes that you use to make a shell cast of bronze, which is poured at 2300 degrees. It’s forever, and the granite underneath it is forever too.”

It’s a very complicated process, but it’s one that Hanlon can handle.

Sculpting has been what Hanlon has done his whole life. He started out doing liturgical statues in churches for about ten years. An eight-foot bonded bronze statue of Jesus on the cross sits in Jackson, N.J. Fr. Pedro Arrupe, S.J. kneels on a six-and-a-half foot statue in Massachusetts at the College of the Holy Cross, and Dorothy Day at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Colts Neck, N.J.

“I have over 200 statues in churches around the nation,” Hanlon said. “Then I turned to sports and found a spiritual connection. It’s tough to deny the pop culture influence on us in sport. It’s part of the fabric of who we are. I did Jackie Robinson as a football player at the Rose Bowl. That’s a spiritual piece. It reeks of humanity”

Hanlon said that he refocused his efforts, and that the world of sports has given him an avenue to show his love for them.

He went to Monmouth University and earned his degree in Art Education in 1988, but he always dreamed of becoming a track coach. His daughter, one of his five children with wife Michele, is now a successful track and cross-country coach. “I think I was a good coach to her,” he said.

In Hanlon’s eyes, every piece he works on is art education.

“I am in fact a walking art history,” he said.

Hanlon’s resume of notable lifelike rendering is long. Aside from Lapchick and Robinson, he has sculpted statues of Shaquille O’Neal, Charles Barkley, Evander Holyfield, Yogi Berra and Bob Cousy. He has emulated the likeness of Susan B. Anthony and first responders, and will have a statue of Harriet Tubman installed in Auburn, N.Y., the city where the abolitionist died and now rests.

The work that stands out to him the most is one he did of his best friend in college. It’s called the “Involved Student.” A girl lies her head on a bag while reading a book and propping her leg on a soccer ball.

The reason?

“I married her and have five kids with her.”

Hanlon hopes to have a statue of former St. John’s coach and legend Lou Carnesecca on campus by the end of this year. He said he did the sculpting of Carnesecca on his own because he admires him more than most of the other coaches he has met.

“He has a beautiful presence about him,” Hanlon said. “He is one of a kind.”

The goal is to eventually create a plaza where Lapchick, Carnesecca and former baseball coach and Athletic Director Emeritus Jack Kaiser are all next to each other.

He wants it done as soon as possible.

“Can you imagine having a Lou Carnesecca dedication without him there?” he asked. “The statue is made. The school needs to pay for the bronze casting, and I will put it up. It looks exactly like him.”

While his career has taken him all over the world, Hanlon is grateful that St. John’s and the program has accepted his work and that it gives those who walk the campus a sense of history behind the man who now oversees Taffner and Carnesecca Arena. He jokingly apologized for the statue he just finished of the Georgetown bulldog, but said that St. John’s will always be special to him.

“I’ve been really lucky, really lucky,” Hanlon said. “Go Johnnies.”